VII. Governance

Frameworks for research integrity

The Status Quo in Europe

Symbol for General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe.(2 April 2018 Author: Dooffy), Wikimedia Commons

Tip:

The Webpage Audiotranskription.de responds to recent changes in Germany’s General Data Protection Regulation (DSGVO) with helpful templates and a checklist for conducting, processing and storing interviews in compliance with the GDPR: https://www.audiotranskription.de/qualitative-Interviews-DSGVO-konform-aufnehmen-und-verarbeiten [in German only!]

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and its implications

- …since its implementation in 2018 regulates data protection and privacy in the European Union (EU) and the European Economic Area (EEA).

- It addresses principles (mainly “fpic”-rules), rights of the ‘data subject’ (e.g. to withdraw consent at any time, the access to and the right to object to the further processing of one’s own data, and their erasure on request).

- It specifies duties of data controllers and processors (e.g. secure storage of data, pseudonymization), and the transfer of personal data outside the EU and EEA areas.

- The General Data Protection Regulation of 2018 directly affects the review process of all EU-funded research projects (-> see following slides).

The Status Quo in Germany (2020)

- For the social sciences (sociology, political science, economics, social and cultural anthropology, educational science and related subjects), the submission of ethics approvals are generally required if patients are involved in the study. An ethical statement is expected, and an ethics vote may be required, if the investigation involves vulnerable groups, such as persons with reduced ability to give their consent. Source: DFG: Förderung. FAQ: Informationen aus den Geistes-und Sozialwissenschaften. Ethikvotum [mytranslation].

- This is to change soon, due to the implementation of the GDPR at national level!

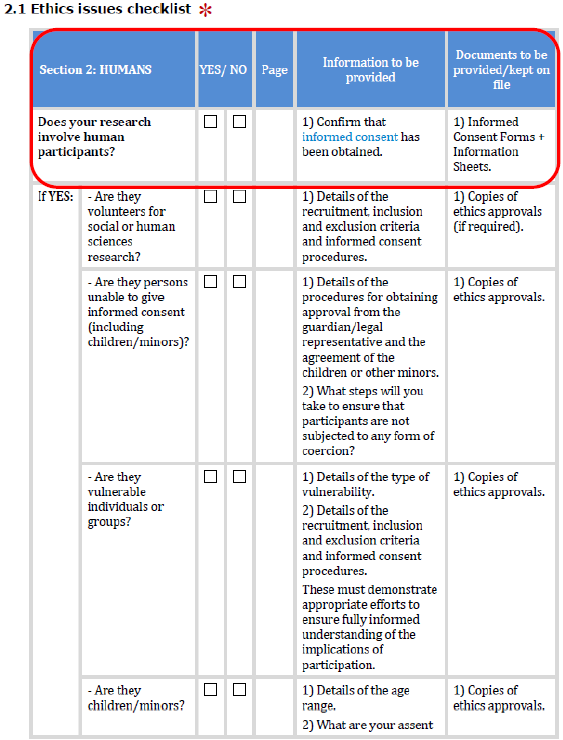

European Research Council (ERC) Ethics Self Assessment (2019)

The ethics issues checklist

* EC 2019: Horizon2020 Programme Guidance. How to complete your ethics self-assessment, p. 6 [Screenshot]

- “Ethics is given the highest priority in EU funded research: all the activities carried out under Horizon 2020 must comply with ethical principles and relevant national, EU and international legislation;

- Consider that ethics issues arise in many areas of research (also social sciences, ethnography, etc.);

- If your proposal raises one of the issues listed in the ethics issue checklist, you must complete the ethics self-assessment;

- Ethics also matter for scholarly publication. Major scientific journals in many areas will increasingly require ethics committee approval before publishing research articles;

- Consider involving/appointing an ethics adviser/ advisory board.” [EC 2018b]

- “If your proposal is not given ethics clearance, it is not eligible for funding and will be rejected.” https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/docs/h2020-funding-guide/grants/from-evaluation-to-grant-signature/grant-preparation/ethics_review_en.htm

Different kinds of informed consent

Written or oral; digital/social media and sensitive data collection; vulnerable participants (LSE 2019)

Tip:

If you are in need of a template for a workable information sheet and „informed consent” form:

LSE (London School of Economics). 2019. Sample Information sheet and consent form

Informed Consent Guidance (LSE 2019)

- “Written consent should be sought wherever possible. Aside from its generally being a better guarantee that participants have indeed given their consent, written consent also provides an auditable record that will prove useful in the event of a dispute or questions arising later regarding the use or storage of data. Research that proposes to use only verbal consent will need to justify why written consent is inappropriate for the study.

- For online surveys, social media platforms or other digital data collection,appropriate ways should be sought to ensure that participants explicitly signal their consent (e.g. by explicitly ticking an “I agree” box).

- [..]Where the research involves sensitive issues (ethnicity, sexual behavior, political beliefs, illegal behavior etc.), special attention should be paid to ensuring that the participants are always fully informed about the risks in taking part, as to the confidentiality and data management of such data.

- [..]Research involving vulnerable participants raises complex ethical issues concerning which it is difficult to formulate generally applicable rules. Researchers should consult relevant guidance and discuss their proposals with those with experience in conducting such research.” (LSE 2019: Informed Consent)

Good reads:

• LSE. 2019. LSE Informed Consent Guidance.

• Dickson-Swift, Virginia. 2008. et al. Undertaking Sensitive Research in the Health and Social Sciences. Managing Boundaries, Emotions and Risks. Victoria: La TrobeUniversity.

• Association of Internet Researchers. 2019. Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.0.

Informed consent guidance in EU funded research

Point to ponder:

Non-written consent can be given e.g. with a finger print, testified by a respected local person who is literate.

But: finger prints fall under the category of sensitive personal (biometric) data.

• Is that a problem; when and how?

• Would alternatives be conceivable?

EU Self assessment guidance: Informed consent (EU2019.Guidance, How to complete your ethics self-assessment).

“Participants must be given an informed consent form and detailed information sheets that:

- are written in a language and in terms they can fully understand

- describe the aims, methods and implications of the research, the nature of the participation and any benefits, risks or discomfort that might ensue

- explicitly state that participation is voluntary and that anyone has the right to refuse to participate and to withdraw their participation, samples or data at any time —without any consequences …

- Participants must normally give their consent in writing (e.g. by signing the informed consent form and information sheets).

- If consent cannot be given in writing, for example because of illiteracy,non-written consent must be formally documented and independently witnessed.”

Good reads:

• Iphofen, Ron. 2013. Research Ethics in Ethnography/Anthropology. Published by the European Commission, DG Research and Innovation. [The standard reference on EC level]

• EC. 2019. Horizon 2020 Programme. Guidance. How to complete your ethics self-assessment. Version 6.1.

• Annechino, Rachelle. 2013. The ethics of openness: How informed is “informed consent”? (Online Journal) [On how much Informed consent is less about forms, than about relationships between people, and trust.] Ethnography matters

Incidental findings and ethical governance

Preserve confidentiality or disclose information to authorities?

Buzz Group:

• Under what circumstances would you disclose incidental findings to responsible or accountable authorities?

• How would you argue, if the funding agency required you to include disclosure of incidental findings in information sheets and consent forms?

• Think in particular of constellations where the political or legal procedures do not follow the usual ideas and principles of equality, human dignity, fundamental rights or separation of powers.

Concerning ‘unintended/unexpected/incidental’ findings (like criminal activities, child or vulnerable adult abuse) the EU Guideline on Ethics in Social Science and Humanities state (EU 2018:14):

- “Fieldwork, observations and interviews can yield information that goes beyond the scope of the research design, thus presenting the researcher with a dilemma: whether to preserve confidentiality or to disclose the information to relevant authorities or services. [..] A characteristic of incidental/unexpected findings is that they require the researcher to take some form of action.

- As a rule, criminal activity witnessed or uncovered in the course of research must be reported to the responsible and appropriate authorities, even if this means overriding commitments to participants to maintain confidentiality and anonymity. [..]

- In some research settings (for example when working with refugees), it may be more appropriate to contact relevant NGOs or agencies with appropriate expertise rather than the authorities.”

Good reads:

• European Commission.2020. Grants: Guidance note — Research on refugees, asylum seekers and migrants: V1.1 — 07.01.2020.. [Shows procedural alternatives in case participants themselves are/would be made vulnerable through disclosure]

• Düwell et al. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.590 (on ethics issues in irregular migration).

Ethical clearance vs. ethnography

Unattainable expectations

Point to ponder:

• Is Delgado’s criticism justified?

• Are there ways out of this ethical quandaries?

Carmen Delgado Luchner in 2017 in her research blog comments on the impossibility of ethnographers meeting the demand for informed consent in institutional ethical review processes, as…:

- “[..]it supposes that the researcher is able to anticipate ‘with whom, for how long, to what end, and where’ she will work (Simpson, 2011: 380), which runs counter to the inductive, iterative and open-ended nature of ethnographic inquiry.

- [..]it is not easy to define who is a participant, i.e. who is affected directly or indirectly by the researcher’s presence in the field.

- [..]obtaining informed consent mainly in order to allow the researcher to protect herself and avoid liability [..] is an unethical use of research ethics.” (Luchner Delgado 2017)

Good reads:

• Lambek, Michael. 2012. Ethics out of the ordinary. In R. Fardon, et al. eds., The SAGE Handbook of Social Anthropology, 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 140–152.

• Mookherjee, Nayanika. 2012. Twenty-first century ethics for audited anthropologists. In R. Fardonet al. (eds.). The SAGE Handbook of Social Anthropology, 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 130–140.

Improper compromises [Donzelli 2019]

- “My analysis highlights how being an ethnographer entails deliberate and methodical forms of surrendering to the unpredictable and the unexpected. Such an apprenticeship (…) entertains a complicated relationship with the growing hegemony of the research protocols of audit cultures.[…]

- Responding (and being held accountable for my answers) to questions that presuppose methods that do not belong in what I consider sound ethnographic practice has required making difficult moral and scientific compromises.” (Donzelli 2019, 17f)

“February 16, 2015, a new message appears in my electronic mailbox. I skim it quickly. A paragraph immediately catches my eye:

- […] We would need to know more specifically about the ethnographic interviewing —how will you recruit participants, what will you tell them about your work, what are the possible risks for participating […]

In the follow up “Checking In On Your Research Study” emails I receive from my University’s IRB, I am periodically asked to fill in the “Continuing Review of Ongoing Research Form,” which contains a set of simple and straightforward questions such as:

- Have you started recruiting participants? If so, detail how many.

- Have any participants withdrawn from the study? If so, detail how many and reason for withdrawal, if known.

- Have there been any changes to your protocol? If so, re-submit the protocol with changes indicated, and any modified informed consent and/or assent forms.

- Have there been any complaints, unexpected events, or protocol deviations related to the research? If so, detail them here.” (Donzelli 2019,2)

Good reads:

• Donzelli, Aurora. 2019. Discovering by Surrendering: for an Epistemology of Serendipity. Against the Neoliberal Ethics of Accountability. In: Antropologia, Vol. 6, Numero 1 n.s., aprile. https://www.ledijournals.com/ojs/index.php/antropologia/article/download/1529/1425.

• Strathern, Marilyn. 2000. ed. Audit Cultures: Anthropological Studies in Accountability, Ethics and the Academy. New York: Routledge. [The classic on audit cultures. Twelve anthropologists map out its effects around the workplace, public and academic institutions in Europe].

• Haggerty, Kevin. 2004. Ethics Creep: Governing Social Science Research in the Name of Ethics. Qualitative Sociology. 27. 391-414. DOI: 10.1023/B:QUAS.0000049239.15922.a3. [an early warning against the negative and homogenising effects of research ethics boards (REB’s) by an insider]

EASA’s Statement on Ownership & Informed Consent (2018)

European Association of Social Anthropologists

Points to ponder:

• “Doing Anthropology Ethically Means Doing Ethics Anthropologically!” (Lederman 2017)

• What’s the message in Rena Lederman’s statement?

• Why does EASA speak of”materials”, and not of “data”?

• Why should ethnographers be exempt from a ‘default’ prior informed consent process?

• What makes their approach special?

- “1. Ownership: Ethnographic materials are coproduced […]. As such, they cannot be fully owned or controlled by researchers, research participants or third parties. The use of standard intellectual property licenses and protocols may not apply to all ethnographic materials.

- 3. Consent: Ethnographic participation in a social milieu can lead to situations [for which] it is often impossible to obtain prior informed consent. […] In contexts of violence or vulnerability, written consent may violate research participants’ privacy and confidentiality, and even put them at risk.

- 4. Custodianship: Researchers have a scientific and ethical responsibility […] that is usually negotiated with research participants. These forms of custodianship […] cannot always be anticipated or pre-formatted.” [EASA 2018]

Good reads:

• “Informed Consent”in anthropological research: http://ethics.americananthro.org/ethics-statement-3-obtain-informed-consent-and-necessary-permissions/;

• The debate on “Informed Consent Without Forms”: C. Fluehr-Lobban(1994): Informed Consent in Anthropological Research: We Are Not Exempt. Human Organization 53 (1): 1-10.

• EASA. 2018. EASA’s Statement on Data Governance in Ethnographic Projects.

• Lederman, Rena.2017. Doing Anthropology Ethically Takes Practice: A US Perspective on the Formalization Question. Von Poser Plenary IV: Doing Anthropology Ethically: Is Formalization the Solution? GAA annual meeting, Berlin. Draft.

Modifying the Informed Consent Process in Ethnographic Studies

The Oral Consent Card of the University of Virginia

“…Where the participant may be uncomfortable with a form and/or unable to use it, the Oral Consent Card provides all of the elements required for consent in a bullet format so that the researcher can refer to each point as he or she is obtaining consent from the participant.”

https://research.virginia.edu/irb-sbs/consent-templates

IRB-SBS Contact Info:

Tonya R. Moon, Ph.D., Chair, Institutional Review Board for the Social and Behavioral Sciences https://research.virginia.edu/irb-sbs

PLEASE MAKE SURE THAT:

- “People understand they are taking part in a research project. They understand what you are asking of them, and they freely consent to participate. You have their permission to use the information you gather about them in the ways you intend.

- People understand what kinds of information you are collecting and what materials you will be carrying away from your interactions with them. They understand how the information will be used in your study and if there is a possibility that the information will be used in future studies.

- People know when you are collecting personal identifying information about them and that you will respect their wishes to have their identity acknowledged or kept confidential.

- People understand the risks they incur in participating in your research and what you are doing to minimize them.

- People know whether their involvement in your research brings them any benefits.

- People know they can opt out of your study at any time, and that they can request that any materials implicating them be destroyed. They know they are free to remain silent on any topic.

- People know that there is someone they can ask if they have any questions or concerns about your research. You should provide them with your contact information, your local advisor’s contact information (where applicable), and the IRB-SBS contact information (where applicable).”

Oral Consent Card, University of Virginia

Alternatives to IRBs and Ethical Guidance Sheets?

Ethical peer mentoring (DGSKA – Germany + Abv – The Netherlands)

DGSKA Homepage: https://en.dgska.de/ethics/

https://en.dgska.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Ethik_Banner.jpg

(Screenshots/Cut outs: M. Schönhuth 2021)

- The DGSKA (German Anthropological Society) offers a “reflection sheet” on issues of research ethics for its members

- “It is meant to be used within the context of mentoring conversations (e.g. between doctoral students and their supervisors) or in peer-to-peer discussions (particularly for advanced specialists in the field).

- The document includes a form which confirms that the discussion has been conducted: this form is for internal use or, if required, it can be submitted to ethics committees as proof of the discussion —however the content of the discussion itself remains confidential.” (https://en.dgska.de/ethics/)

- “The ABv (Dutch Anthropological Association) encourages researchers to discuss among each other, on a regular basis, their ethical choices and decisions, and to provide transparency about their methods, research process and data analysis.

- Especially for researchers who work on similar topics or in similar fields, discussing not only the contents of their studies, but also the ethical considerations involved, could be very valuable.” (ABv. 2019. Code of Ethics)

Good reads:

for the recent discussion in German-language anthropology, see:

• Hornbacher 2013 (ed.): https://www.ethnologie.uni-hamburg.de/forschung/publikationen/ethnoscripts/es-15-2.html

• Dilger 2017 Ethics, epistemology, and ethnography. DOI: 10.3790/soc.67.2.191; with comments by Hornbacher 2017 and Alex 2017.

Ethical peer mentoring + certification process (ASAA/New Zealand)

Screenshot from the ASAA/NZ Homepage (M. Schönhuth 2021)

| Photo by Caroline Bennett, 2015 (Cambodia)

Association of Social Anthropologists of Aotearoa / New Zealand

- Basis: Principles of Professional Responsibility and Ethical Conduct©1992

- Peer review process: ASAA/NZ provides members with peer guidance by offering an ethical review of research proposals.

- Ethics board process: only if peer reviewers detect problems, does the Ethics Comittee review the proposal and provide further feedback and discussion.

- Certification process: if external agencies require certification of ethical review as a prerequisite for funding or permission to conduct research, the ASAA/NZ Ethics Committe will write a letter to the agency outlining the ethics review procedure and reporting on the proposal. [see: ASAA/NZ Ethical Review of Research Proposals]

- note: ASAA/NZ is a relatively small association, with some 100 members!

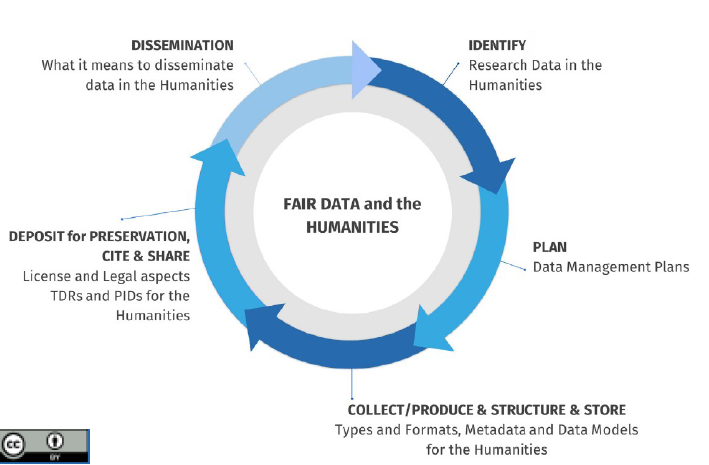

Data Management Plan

FAIR (“Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable”) principles in the Humanities (ALLEA)

Key phrases of the data management lifecycle, ALLEA Report Feb. 2020 :6

- ALLEA 2020: Sustainable and FAIR Data Sharing in the Humanities. ALLEA Report. Berlin.

- An All European Academics (ALLEA’s) working group on E-Humanities, has produced a report with a series of recommendations, for how Humanities researchers can make their research outputs FAIR: Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. Some recommendations:

- “Think of all your research assets as research data that could be potentially reused by other scholars. Consider how useful it would be for your own work if others shared their data.”[:9]

- “Legislation: Which national legislation applies to other researchers’ work I use in my project? Do I have the right to collect, preserve and provide access to the data of my project? [..] Are there risks of exposing the identity of human participants in my study? Am I allowed to digitally reproduce material and (re-)publish it in a digital reproduction?” [:21]

- The whole report can be downloaded here

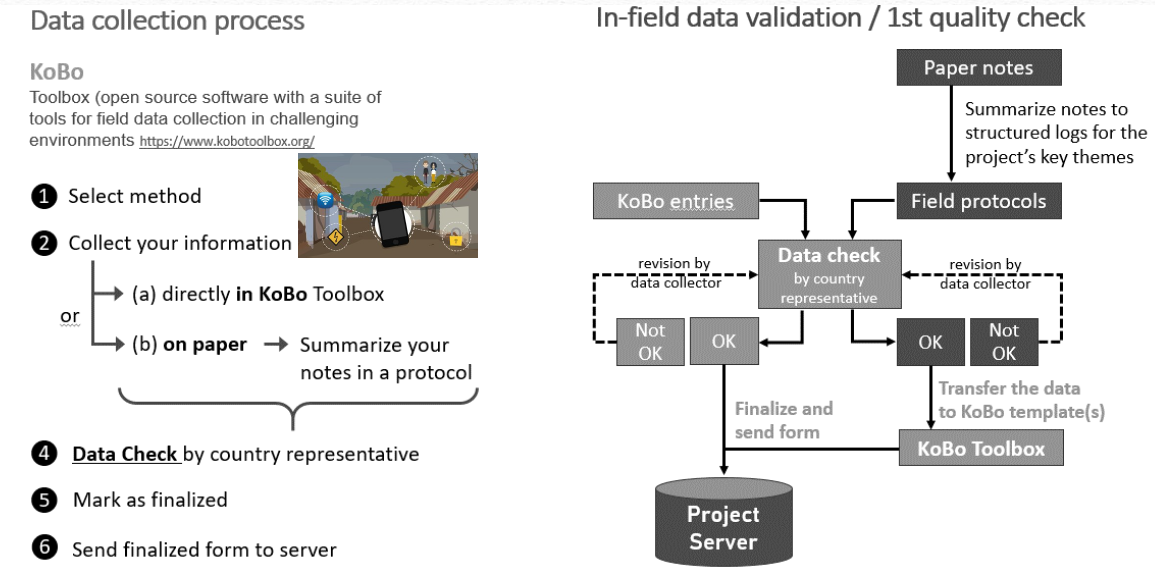

Example: Data collection process in a team based international research project (TRAFIG)*

* reprint with kind permission of TRAFIG (Transnational Figurations of Displacement), an EU-funded Horizon 2020 research and innovation project.

* Download the KoBo Toolbox for free here

Data Management and Ethics in Ethnographic Research (2018+)

dgv (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Volkskunde):

- Research “[..] is conceived as an open process that is situation-and observer-dependent. Interlocutors are not conceptualized as “study participants” and are rarely recruited as samples; rather, they are regarded as members of a social context to which they grant researchers access and to whom they have rights. …Collaborative forms of knowledge production and representation are increasingly being developed. Accordingly, the relationship …is understood as a mutual trusting relationship, which forms the fragile basis of many field research projects. [..] The dgv… does not support a uniform, unconditional obligation to archive and make available data for subsequent use.” (dgv. 2018)

EASA (European Society of Social Anthropologists)

Point 2 and 5 out of six, placing ethnographic research within the special clause on ‚academic expression‘ included in the Article 85(2) of the GDPR

- 2. Archiving: In ethnographic research “data” are always part of a social relationship. As such, it may not always be possible to archive or store research materials, (or it will) require specific technical features (e.g. different roles for access, editing, sharing or privacy) not available in most institutional repositories.

- 5. Embargo: Researchers have a special duty to consider controlling third party access to ethnographic materials and retain the rights of embargo and confidentiality over those materials that cannot be anonymized or turned into data entries. (EASA. 2018. EASA’s Statement on Data Governance in Ethnographic Projects)

Good reads:

• on the essential protection of raw data see http://ethics.americananthro.org/ethics-statement-6-protect-and-preserve-your-records/

• on the ethically justifiable limitations of the dissemination of research results see: http://ethics.americananthro.org/ethics-statement-5-make-your-results-accessible/

• on the problematic of long-term data archiving see: Pels, Peter et al. (2018); and Dilger et al. 2018. DOI: 10.1177/1466138118819018.

• on the use of digitalization and of digital media for data storage and preservation : AAA. 2012. 6. Protect and Preserve Your Records

Hugh Gusterson, “What’s in a Laptop?”Anthropology Now 4, no. 1 (2012):26-31.

Indigenous Data Governance

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) 2020

Buzz Group:

• Besides an ethical obligation: what reasons could speak in favor of a post-project engagementfor you as a researcher?

• Collect arguments in favor of such a commitment, but also difficulties and dilemmas that could arise from it.

- Indigenous Data Governance: “Indigenous data that is, or should be, governed and owned by Indigenous peoples from the very creation of data to its collection, access, analysis, interpretation, management, dissemination, potential future use and storage.”

- Storage and Archiving: “To ensure the longevity and appropriate accessibility of the information, it is essential that data is archived and managed well, and is done in accordance with the requirements of Indigenous stakeholders.”

- Post-project engagement: “It is essential that the research continues to comply with agreements made with Indigenous partners and stakeholders regardless of changes in personnel, staff or university base.” (AIATSIS 2020 :28-31)

Good reads:

• AIATSIS n.d.[2019]. Revision of the AIATSIS guidelines for ethical research in Australian indigenous studies. Consultation draft.

[You’ll also find answers to the buzz group question there].

• AIATSIS. 2020a. AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research (the AIATSIS Code).

• AIATSIS. 2020b. A Guide to applying the AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research

When it comes to vulnerability of research participants, you might be asked by ethics committees to answer questions like the following:

“What impact could the participation of your interlocutors have on their vulnerability, during your field stay and after the results have been published? Could your conclusions backfire and make partcipants more vulnerable, even in their own community, as other community members saw they participated in your study? What steps have you already taken or will you take to prevent this?

The German Anthropological Association (GAA) in 2019 has adopted a “Position Paper on the Handling of Anthropological Research Data”. The paper notes, that “(a)s a general rule, anthropological data cannot be published or made freely available. It is also important to consider the fundamental dilemma that, due to its high level of situatedness, even the controlled provision of data to third parties can only happen on a voluntary basis and after careful consideration of these criteria and standards.” https://en.dgska.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Positionspapier_Bearbeitet-fu%CC%88r-MV_EN_29.11.2019.pdf

For an example of a data governance framework for ethnographic research, see Corsín Jiménez, A. (2018) Data

Governance Framework for Ethnography v 1.0, Madrid: CSIC.

Given the contradictions associated with FAIR principles for local/indigenous communities in seeking control over their own knowledge resources the Global Digital Data Alliance

has launched “CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance”: “The current movement toward open data and open science does not fully engage with Indigenous Peoples rights and interests. Existing principles within the open data movement (e.g. FAIR: findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable) primarily focus on characteristics of data that will facilitate increased data sharing among entities while ignoring power differentials and historical contexts. The emphasis on greater data sharing alone creates a tension for Indigenous Peoples who are also asserting greater control over the application and use of Indigenous data and Indigenous Knowledge for collective benefit.”

This includes the right to create value from Indigenous data in ways that are grounded in Indigenous worldviews and realise opportunities within the knowledge economy. The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance are people and purpose-oriented, reflecting the crucial role of data in advancing Indigenous innovation and self-determination. These principles complement the existing FAIR principles encouraging open and other data movements to consider both people and purpose in their advocacy and pursuits.

https://www.gida-global.org/care

The name of the organization reads:

Global Indigenous Data Alliance (sorry!)