III. Field Conduct

Before you start fieldwork

Dry paddling

“When we choose a research question, that very opening move contains ethical concerns. These ethical concerns are directed primarily towards our general audience for whom this study will be of interest.” (PERCS 2018)

Tips:

• „Review the existing empirical (field) literature on your topic

• What were the limitations of those studies?

• What were the problems they faced?

• Will you be able to avoid the same? (PERCS 2018)

Point to ponder:

• How can we predict some of the possible ethical pitfalls before we even start our research endeavour? (PERCS 2018)

Good read:

• Knapp, Rimasara Kuyakanon. 2020. When does fieldwork begin? Negotiating pre-field ethical challenges. In: Fieldwork in the global south. Jenny Lunn (ed.). London: Routledge, 13-24.

Drawing the line – responsibility to yourself – Safety and Security Measures

Tip:

• To be aware of security measures to be taken there are Risk Assessment sheets with questions in the form of checklists online, which can be answered, such as:

• School of Anthropology (Oxford)

• Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sozial- und Kulturanthropologie (DGSKA)

Extra-Tip: COVID-19 risk minimizing measures

The Safety and Security Guidelines of the EU-sponsored LICCI project contain a section with COVID-19 risk minimizing measures during fieldwork – also with field site-speific measures for more than 30 countries.

In a blog on her fieldwork in the transgender pornography industry in two American cities, Sophie Pezzutto, an anthropology PhD candidate, reflects on where to draw personal lines:

- “Where do I as an ethnographer draw the line between career and personal wellbeing at home and in the field? How much participation is ‘enough’ to get me sufficiently high-quality data?”

- [..]The anthropologist’s dedication to ‘participation’ –to truly understand, to throw off the false lab coat of objectivity and get involved –is one of the discipline’s strong suits. It had always attracted me.

- At the same time, however, the trope of the anthropologist-adventurer is so pervasive, that choosing a safer methodology or more ‘mundane’ field site regularly evokes feelings of guilt.” [Pezzutto 2019]

- -> Sophie in the end found her line and succeeded with her research….

- The German working group on Medical Anthropology recommends: “If dangers come to pass that might gravely affect one’s physical or psychological health, responsibility towards oneself means that one should seriously consider terminating the research.”(AG Medical Anthropology.2005.)

Good reads:

• Pezzutto, Sophie. 2019. I did it for the data. Blog: The Familiar Strange. July 15, 2019.

• Downey, Hillary et al. 2007. Researching Vulnerability: what about the researcher? European Journal of Marketing 4,7/8, 734-39.

• Goldstein, D. M. 2014. Qualitative Research in Dangerous Places: Becoming an ‘Ethnographer’ of Violence and Personal Safety, DSD Working Papers on Research Security: No. 1,

• Koonings, Keeset al. 2019. eds. Ethnography as Risky Business: Field Research in Violent and Sensitive Contexts. Lexington Books.

Training and mentoring schemes for prospective fieldworkers and returnees

Points to ponder:

• Strauss argues for experience based trainings given by accomplished fieldworkers to prepare students for unsettling situations before – and reflect on those after completion of fieldwork (to work on traumas and prevent negative stereotyping). (Strauss 2015: 88; 2017)

• Pollard proposes a mentoring scheme, where post-fieldwork students would act as mentors for pre-fieldwork students; „[…] premised on the idea that PhD students need support from people who understand enthnographic fieldwork, but who have as little power as possible over their professional careers.“ (Pollard 2009: 23)

• How are you prepared / how do you prepare students for fieldwork? Would the proposals by Strauss and Pollard be implementable in your instution?

- In interviews with 16 young PhD candidates on difficulties in fieldwork Amy Pollard identified 16 ‘feelings’ of being: “alone, ashamed, bereaved, betrayed, depressed, desperate, disappointed, disturbed, embarrassed, fearful, frustrated, guilty, harassed, homeless, paranoid, regretful, silenced, stressed, trapped, uncomfortable, unprepared, unsupported, and unwell.” (Pollard 2009: 1)

- Her paper elaborates on every one of these feelings and “[..]concludes with a set of questions for prospective fieldworkers,a reflection on the dilemmasfaced by supervisors and university departments, and a proposal for action.” (Pollard 2009: 1)

Tip:

Check if there is an organization in your home country, such as the Centre for Safety and Development in the Netherlands, that offers safety and security courses for professionals before their employment abroad.

(see: https://centreforsafety.org/universities-research-institutes/ ,C. Jacobs oral inf.)

Good reads:

• Pollard, Amy. 2009. ‘Field of screams: Difficulty and ethnographic fieldwork’. Anthropology Matters, 11,2, 1-24.

• Strauss, Annika. 2015. Beyond the Black Box and Therapy Culture. Verstörende Feldforschungserfahrungen als Zugang zu lokalem Wissen verstehen lernen. Curare 38,1+2,87-102. (German!).

The need for an emergency phone

Emergency phone on the beach at Trefor, North Wales.

18/12/2005. Author: Velela.

Wikimedia Commons

- After some disturbing encounters in the first six weeks of my fieldwork in the northern region of Ghana in the late 1980s, I locked myself up in a house of expatriate friends in the capital for a week and did not leave the premises once during this time.

- Everything inside me was reluctant to re-enter this continent, which at that point of time appeared dark, closed and hostile to me.

- Even if this was followed by an often rewarding and delightful period of fieldwork, there were moments when I wished I could talk to a good friend or share situations with fellow fieldworkers. Due to the lack of transcontinental telephone connections (mobile phones did not exist at that time), I only managed to make one phone call home in eight months.

- Later I framed these disturbing moments as “rites of passage” that you have to endure to be admitted to the halls of professional anthropology. Nevertheless, I bear the scars…

- Tips: contact colleagues who did research in the region before you! Leave a “in case of emergency list” with information about health and travel insurance, passport number, blood group, contact persons, travel itinerary with a trusted person in your country of research (Tip: C. Jacobs)”

Buzz Group:

• Does your institution have an emergency system for ‘stranded’ field researchers, and if so, what does it look like?

• What private network could you create before you leave, so that you don’t get lost or stand alone in critical field situations?

• What sort of safe spaces could you create for yourself, while being in the field?

• Could we also conceive of ‘unsettling field encounters as an access to local knowledge’ (Strauss 2015), and if so, how?

Good reads:

• Davies, James and Dimitrina Spencer.2010. eds. Emotions in the Field: The Psychology and Anthropology of Fieldwork Experience. Stanford University Press. [The contributors show how emotions “…evoked during fieldwork can be used to inform how we understand people, communities, and interactions…”(Davies: Introduction)]

• Thomson, Susan et al. 2013. eds. The Story Behind the Findings. Emotional and Ethical Challenges for Field Research in Africa. Palgrave [on-the-ground anthropological accounts on ethical challenges and pitfalls engaging in local-level research in difficult situations].

“Look, I am a foreigner…!”

Fritz Morgenthaler 1984: Gespräche am sterbenden Fluss, Frontpage. Photo: M.Schönhuth

Buzz Group:

• Read the short account by Fritz Morgenthaler in New York on the right

• What is the message?

• How would you judge his behavior?

• How would this be received in your country, or in the country where you (want to) do research?

• Think of power differentials, gender, colour, status, public/private spaces etc.

“I moved into a small room in New York. [..] In the morning I wanted to have a coffee in the drug store across the street. I stood at the bar. Most people drank their coffee standing up and reading their newspaper. The (waiter) looked at me, pushed his lower lip slightly over his upper lip and raised his chin. I recognized the gesture as a sign and called out to him: ‘A coffee please … without sugar and a little milk only’. A brief rattle and clatter of dishes, cutlery and machines: In front of me stood a glass of light brown, sugared coffee. In the following days all my attempts to have my way failed. After the word ‘coffee’ the waiter turned away before I had even finished my sentence about sugar and milk, and the same drink was always standing in front of me. Then one morning it dawned on me that I could do it differently. When the waiter wanted to serve me, I said loud and clear: ‘Look , I`m a foreigner’. The effect was amazing. The people next to me looked up from their newspapers and looked at me while the waiter waited somewhat perplexed to hear what I was about to say. There was a pause and I felt as if I was standing on a hill and looking into a wide plain in front of me. I said, ‘I am not American, you know. I would like to have a coffee without sugar and a little milk only. ‘Of course, sir,’ replied the waiter. A man next to me put his newspaper aside and began a conversation. He wanted to know where I came from and whether I liked the United States. A glass of dark, unsweetened coffee was standing in front of me.” Fritz Morgenthaler 1984: in: ders et al. (ed.) Gespräche am sterbenden Fluss, p. 9-10 (my translation).

10 Tips for the pre-fieldwork candidate

Upon completion of a one-year fieldwork in Java, Indonesia, Jessica Tremblay compiled ten useful tips for pre-fieldwork candidates “[..]to adapt to their surroundings for surviving anthropological fieldwork.” (I particularly like tips 1, 5, 6, and 10)[Jessica Tremblay. 2014. 10 Tips for Surviving Anthropological Fieldwork]

10 Tips

- Choose a site you won’t hate: make sure that you pick one you will potentially enjoy (depending on your objectives).

- Besides the lingua franca, learn some of the local language. It helps to build rapport.

- Pay attention to gender norms (observe/ respect local etiquette).

- Don’t take things so personally (be fair and be friendly while knowing your limits).

- Harness the power of your introversion (sit and observe, sip your local tea “rather than force an awkward action”.

- Have fun: “Make sure to do things that please you and that take your mind off of your work. Read trashy or good novels (Malinowski did it, ain’t no shame in it)”, go for a swim, build sand castles….

- Find a routine that works for you (and take into account the daily routines of your interlocutors).

- Keep a log book (left side for planning your day, right side for what you accomplished, whom you met, or what you failed to do).

- Never reject an invitation without reason (nevertheless, reject those from whom you feel uncomfortable).

- Become a ‘foodie’ (start cooking yourself and invite people over; share recipes; it’s a great opportunity for socializing) (Tremblay 2014)

Do No Harm

Your responsibility towards research participants

Tips:

-> try to anticipate the long-term effects of your research on individuals or groups

-> consult colleagues, friends, assistants, interlocutors for insight into what risks (and benefits) might matter to local people (Fujii 2012).

-> avoid undue intrusion!

-> worry, even if your interlocutors/reserach particpants won’t!

-> AIATSIS has produced a Protocol with questions, in which particularly distress and psychological harms of participants are envisioned: AIATSIS (2020/07/31; Draft): Guide to a distress protocol

“Among the most serious harms that [one] should seek to avoid are harm to dignity, and to bodily and material well-being of people, especially when research is conducted among vulnerable populations. When it conflicts with other responsibilities, this primary obligation can supersede the goal of seeking new knowledge and can lead to decisions to not undertake or to discontinue a project. Determining harms […] must be sustained throughout the course of any project.“(AAA 2012)

Individual Exercise

• Take your own or a hypothetical field project:

• Hypothesize one worst-case scenario which could happen through your presence/research steps in the field. How might you deal with them?

• Then develop less dramatic and more realistic scenarios. How might you deal with them?

• It might help to place yourself in various roles in the social setting, playing the role of the participant (a child, mother of 4 kids, minority member, homeless person) and not just the researcher. (PECRS 2018)

Good reads:

• Anderson, Mary B. 1999. Do No Harm: How Aid Can Support Peace—or War. [The classic on the Do-no-harm principle in development aid].

• Do-No-Harm-prerequistes in anthropological research: cf. AAA 2012.

• Dutch Anthropological Association.2019. Ethical Guidelines: Avoiding Harm.

Anticipating Harms

Vulnerability

Tips

Questions ethics review committees may ask:

• Can the selection of interviewees lead to greater vulnerability of individuals within the community (e.g. because they have passed on knowledge that does not legitimately “belong” to them)?

• Are there social inequalities that could be aggravated by the inclusion or exclusion of participants?

• How can you ensure that participants are not directly or indirectly recognizable in the publication of research results (even by other community members)?

- The concept of vulnerability, since its introduction in a bioethics report in 1979, is given highest priority in national and international ethics policies, guidelines and review boards for medical and social sciences (for an overview see. Bracken-Roche et al. 2017)

- Vulnerability (as a subject’s lack of ability to protect their own interests) presents itself in different ways: cognitive and communicative (e.g. because participants are children, or illiterate); institutional(e.g. because participants as employees/prisoners might be called on/forced to join); structural (belonging to a particular social or cultural group/ minority); personal (by a felt obligation; e.g. through patron/client wife/husband relationship).

- It may also derive from limited access to social goods, such as rights, opportunities, and power (lacking agency, autonomy) (For a detailed list of vulnerability areas see. Univ. of Virginia. n.d.

- The key question for any ethical review is: “Are these subjects made any more vulnerable than they might ordinarily be in their daily lives as a result of their participation in this research?“ (Iphofen2013:49)

- The key problem is: who defines who is vulnerable and based on what premises?

Good reads:

• Shitangsu Kumar Paul. 2013. Vulnerability concepts and its application in various fields: a review on geographical perspective. Journal of Life and Earth Science, 8: 0-0, [shows significant variations in the use of the vulnerability concept across disciplines]

• Bashir, Nadia. 2019. The qualitative researcher: the flip side of the research encounter with vulnerable people. Qualitative Research, Dec. DOI: 10.1177/1468794119884805 [on the vulnerability of the researcher in the field encounter]

• Menih, Helena. 2013. Applying Ethical Principles in Researching Vulnerable Population: Homeless Women in Brisbane. [on exclusion criteria and participant-researcher relationship]

Who counts as vulnerable? The ‘vulnerability trap’

Göttke et al. on a website about ‘science, medicine and anthropology’ discuss different ranges of the concept of vulnerability in national discourses:

Pregnant woman at a WIC clinic in Virginia. Author: Ken Hammond (USDA)

Upload Date: 13/11/ 2002 (Public Domain). Source

- “For example, in the US, pregnant women are deemed a ‘vulnerable population,’ whose participation in research must be carefully monitored.” [eg. NBAC 2001 , my comment, ms]

- “In the Netherlands, where most pregnancies are handled by midwives and not doctors, there is broad encouragement to not overmedicalizepregnancy, and the inherent vulnerability of pregnant women is not presumed.

- Categorizing pregnant women as ‘vulnerable’ when not backing this with mandated federal maternity leave might, from the vantage of the Netherlands, be seen as unethical rather than protective.” (Göttke et al. 2013.)

- Virokannas et al. in an overview propose to focus on vulnerable life situations, instead of vulnerable groups or individuals and “…to recognise the temporal, situational, relational, and structural nature of vulnerability.”(Virokannas et al. 2018:336)

Point to ponder:

• What if interlocutors categorized as ‘vulnerable’ refuse to be ‘protected’?

• Would they not be made be vulnerable again by exclusion?

Good reads:

• Virokannas, Elina, Suvi Liuski & Marjo Kuronen. 2018. The contested concept of vulnerability – a literature review, European Journal of Social Work

• Kirmayer, Laurence J. 2013. Foreword. In Karen Block et al. (eds.) Values and vulnerabilities: The ethics of research with refugees and asylum seekers, v-ix. (On a special patronizing form of an ‘ethics of vulnerability’ prevalent in refugee studies).

• Dittmer, Cordula & Daniel F. Lorenz. 2018. Forschen im Kontext von Vulnerabilität und extremem Leid – Ethische Fragen der sozialwiss. Katastrophenforschung. FQS, 19(3), Art. 20, (German!)

Intervene or not?

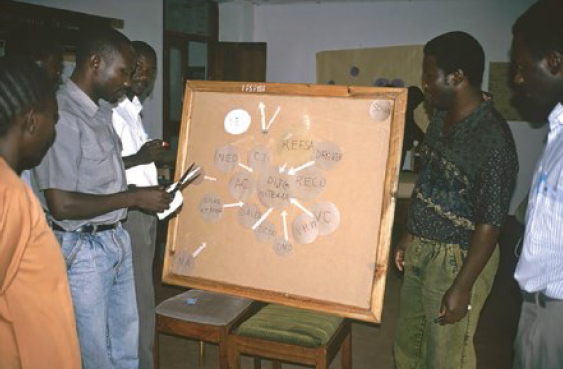

Stakeholder Mapping Exercise with the district team /Tanzania (© Schönhuth 1997)

- District team members work on a visual stakeholder diagram of their community development project. Circles represent stakeholders; size indicates importance; the proximity to the center shows their perceived performance; arrows point to desired change (towards the center = more influence/ towards the outside = less influence).

- The exercise was designed to familiarize the district team with participatory assessment tools using their own project as an example.

- The perceived importance and performance of their superiors is also reflected in the diagram.

- At the end of the exercise, the district team is eager to show the map at the final meeting with their superiors at the regional level.

- Point to ponder: As a researcher / facilitator of the exercise, how would you react? Think about status differentials, face keeping rules, unwanted consequences for group members –but also the “vulnerability trap” (see above)

Good reads:

• FAO. n.d.Conducting a PRA Training and Modifying PRA Tools to Your Needs. Chap.6.2.5. Venn Diagram on Institutions.

• Schönhuth, Michael. 2009. Participatory Appraisal of a Personal Network with VennMaker.

Local Norms of Conduct

If you are invited to somebody’s home: What rules apply? Where? When?

“Open is Welcoming” by Alan Levine, CCO https://creativecommons.org/2017/09/05/invitation-join-cc-open-education-platform/

Learning Local Norms of Conduct

Whether or not to participate in a religious ceremony

Buzz Group:

Evaluating the Options

• “What are the degrees of harm that will ensue if you choose one path or the other?

• Is sitting quietly less risky than joining in?

• Or vice versa?

• Can you avoid an either/or dilemma and identify a compromise that allows you to avoid offending either side?” (PERCS 2018).

- “You are working with a local church congregation and are present during many of their religious ceremonies. You are not a member of the church. Everyone is clapping and singing while you sit quietly in your pew. Eventually, everyone moves to the altar to accept communion.

- You don’t want people to think you do not approve of the way they worship, nor do you want people to think you are presumptuous by participating.

- Do you participate in the ceremony by clapping and singing and eventually receiving communion?

- Or do you remain a quiet and detached observer?” (PERCS 2018) Evaluating the options ; Fieldworkers weigh in

Good reads:

• Knibbe, Kim. 2020. Is critique possible in the study of lived religion? Anthropological and feminist reflections, Journal of Contemporary Religion,35:2, 251-268, DOI: 10.1080/13537903.2020.1759904. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13537903.2020.1759904?needAccess=true. [shows how the “commitment to developing non-reductionist approaches to lived religion should not come at the cost of overlooking and failing to develop critical feminist perspectives, from a relational and situated epistemology” (Knibbe2020: 265),

• Rodemeier, Susanne. 2015. Herausforderungen bei der Erforschung von Christen charismatischer Pfingstkirchen auf Java, Indonesien. Curare 38, 1+2:134-146. [addresses the pressure that inerlocutors put on the researcher by treating her as a potential proselyte and the need for an unexpected sensitive approach – in German!].

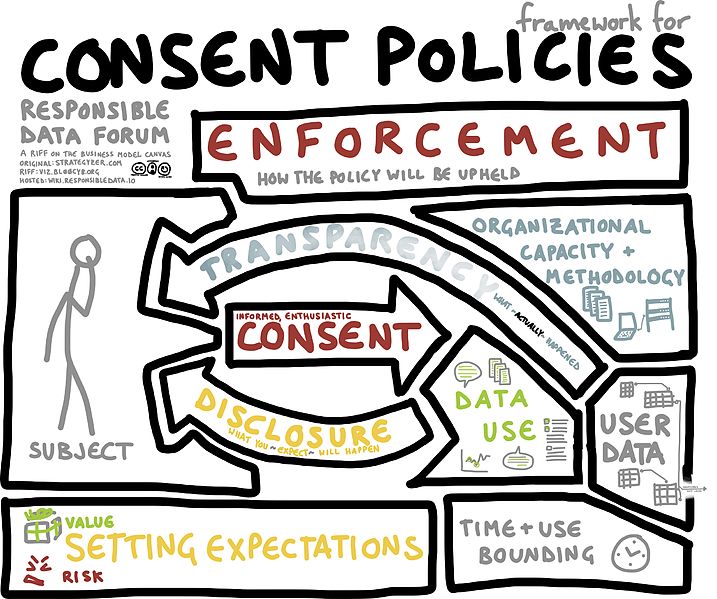

Informed Consent

Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC)

Buzz Group:

• In ethnographic research the dynamics of the inquiry develop in the field. Readiness to inform the researcher about local life and knowledge grows with mutual trust.

• “Consent becomes a negotiated and lengthy process –of mutual learning and reciprocal exchange, rather than a once-for-all event. […] Needless to say, the conventional ‘consent form’ is so irrelevant as to be a nuisance to all parties.” (Wax 1980:275)

• Do you agree with Wax’s assessment?

• Can the FPIC rule be implemented in ethnographic research at all?

- Invented as a reaction to medical malpractice in the 1950s, “Informed consent” since then describes the process for getting permission to disclose any personal information of research participants or for a planned (medical) intervention on a person.

- Consent “[..]presumes that the person’s participation in the study is voluntary—that the person has not been pressured, coerced, or tricked into participating” (Fujii 2012:718).

- The standard, Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) is embedded in the discussion on Indigenous Peoples’ rights and framed in a series of internationally binding legal instruments (e.g. the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples or ILO C169 – for an overview see: Wilson 2016: 3).

- “In short, consent should be sought before any project, plan or action takes place (prior), it should be independently decided upon (free) -and based on accurate, timely and sufficient information provided in a culturally appropriate way (informed) -for it to be considered a valid result or outcome of a collective decision making process.”(FAO 2016).

Good reads:

• Bell, Kirsten. 2014. “Resisting Commensurability: Against Informed Consent as an Anthropological Virtue.” American Anthropologist 116(3):511–22.

• Faden, Ruth R. et al. 1986. A History and Theory of Informed Consent. New York: Oxford University Press.

• Wax, Murray, L. 1980. Paradoxes of ‘Consent’ to the Practice of Fieldwork. Social Problems, Feb. 27,3, 272-283. [for me still one of the most comprehensive and illuminating articles on the topic].

• FAO. 2016. Free Prior and Informed Consent. An indigenous peoples’ right and a good practice for local communities. Manual for Practitioners.

The pitfalls of informed consent

Fujii, referring to a study by Ivy Goduka on black child development under apartheid in South Africa, suggests:

- “How does a researcher secure informed consent when more than half of the subjects in her study are illiterate and not familiar with research enterprises? Such people may think that refusing to participate would create problemsfor them and their children. […]

- On the other hand, agreeing to participate may reflect their submission to the school, or to the researcher, who represent authorityin the eyes of black families […]

- People may consent not only because of social pressure, but also because they believe that establishing a relationship with the researcher will be beneficial in and of itself. […]

- In extremely poor, marginalized, or illiterate communities, people may view the researcher as a valuable patron—someone who can provide tangible benefits, such as financial aid, legal assistance, and job referrals.” [Fujii 2012:719; based on Goduka 1990] -> for the last two bullet points see also the respective charts under “Negotiation”

Extra Tip:

What an FPIC process could look like working with indigenous communities can be followed up in an informative and practical paper of the Árran Lule Sami Centre on FPIC-key elements, challenges and recommendations handling resource extraction in the Arctic (Wilson 2016)

Good reads:

• Fujii, Lee Ann. 2012. Research Ethics 101: Dilemmas and Responsibilities. PS: Political Science & Politics, 45,4, 717-723. doi:10.1017/S1049096512000819. ->Downloadable!

• Goduka, Ivy N. 1990. “Ethics and Politics of Field Research in South Africa.” Social Problems 37,3: 329–40.

• Jacobs, Carolien. 2020. Getting prior informed consent – a thorny issue. TRAFIG Blog [on the pitfalls of upward accountability and downward transparency getting fpic during in fieldwork in the DRC.]

“Getting prior informed consent – a thorny issue” (by Carolien Jacobs)

Refugees in Congo, Author: Julien Harneis, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons (Source)

- “Asking people about their lives and taking note of personal details often raises expectations about the provision of aid. Indeed, many people equate interviews with needs assessment and subsequent aid provision.

- Getting a written informed consent, i.e. asking for signatures, makes interviews more formal and feeds this impression further…: ‘If there is an interview, or if you have heard a lot of bullets at night, you know that aid is coming’ [..] If you expect to receive aid, it is better to present yourself as even more vulnerable as you actually are. [..]

- Getting a signature [..]is mostly a way of rendering upward transparency, but is not helpful in practice, sometimes even unhelpful and not necessarily increasing transparency towards our respondents.

- As a team, we are committed to make use of the forms, keeping in mind that we have to do our best to find a balance between upward accountability, downward transparency, and research interests in an optimal way. The coming months will show us how best to strike this balance!” (Carolien Jacobs 2020 on the dilemmas of upward accountability and downward transparency getting fpic during fieldwork within the framework of a major EU research project in the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

Good read:

• Jacobs, Carolien. 2020. Getting prior informed consent – a thorny issue. TRAFIG Blog: https://trafig.eu/blog/getting-prior-informed-consent-a-thorny-issue.

Rights to confidentiality and anonymity

…and ethnographic peculiarities

Tips / Points to ponder

• “Researchers should take appropriate measures relating to the storage and security of records during and after fieldwork.” (ASA 2011)

• “Researchers should use -where appropriate -the removal of identifiers, the use of pseudonyms and other technical solutions in field records and in oral and written forms (whether or not this is enjoined by law or administrative regulation!“ (ASA 2011)

• “Care should be taken not to infringe uninvited upon the ‘private space’ (as locally defined) of an individual or group.” (ASA 2011)

• What storage/security measures during fieldwork do you know/use?

• Do you have experience with the removal of identifiers in field records (including field diaries)?

With regard to confidentiality and anonymity the ethical guidelines for good research practice of the Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and the Commonwealth (ASA) in 2011 state:

“Informants and other research participants should have the right to remain anonymous and to have their rights to privacy and confidentiality respected.

However, privacy and confidentiality present ethnographers, working across cultures, with particularly difficult problems, given the cultural and legal variations between societies.

Also there are various grades in which the research role of the ethnographer may be realized by some or all of participants or may even become ‘invisible’ over time.” (ASA. 2011 Ethical Guidelines for Good Research Practice)

Public space – private space: human universal – cultural variations

Funeral procession of Buddhist monks before lighting the pyre for cremation in Don Det, Laos; by: Basile Morin© CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikipedia.

Christian funeral procession by car in Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, England, 2009 Public Domain, Wikipedia.

Point to ponder: Have you come across situations, in which you encountered surprising “unusual” borders between public and private/personal spaces working across cultures ?

Incidental findings – Buzz Group

Young mother with Newborn in seclusion hut / South India © Schönhuth 2002

- You are on a walk back from an interview in one of the villages that opened up their doors for your field research.

- You come across this hut, near the village garbage dump. Inside there is a young mother with her newborn child. You are confused!

- Your key informant explains that this is a postnatal seclusion hut where the woman – according to the local tradition – has to spend two months separated from the community, because of her ‘impure condition’. Some villages have abandoned the tradition, in others, like yours, village elders insist on keeping it to hinder ‘modernist influences’.

- You know a journalist in town who regularly blames local politicians for not doing anything against women’s rights violations in the countryside.

- Should you inform the journalist? Should you go to the police? Should you discuss the topic with the local elders? Or should you respect your hosts and their traditions and keep silent?

- Think of the consequences for the different stakeholders involved. What behavioral alternatives are there for the fieldworker?

Overriding ethical reasons not to give a warranty?

Anonymous with Guy Fawkes masks at the Scientology area in Los Angeles. Author: Vincent Diamante.10 February 2008, Commons Wikimedia

“If guarantees of privacy and confidentiality are made, they must be honored – unless there are clear and overriding ethical reasons not to do so.” (ASA 2011. Ethical Guidelines for Good Research Practice)

Points to ponder:

• What could be “overriding ethical reasons” not to honor guaranteed confidentiality?

• Do you know cases in which anonymization failed?

• Can you think of situations in which the general right to privacy collides with (scientific) public’s interest in information? (powerholders / public persons)?

• What if some participants want to be credited with their full names in publications, but others don’t?

Good reads:

• On the issue of anonymization of research partners. Sue-Ellen Jacobs, “Case 6: Anonymity Revisited”.

• and: “Case 5: Anonymity Declined,” in Handbook on Ethical Issues in Anthropology, ed. Joan Cassell and Sue-Ellen Jacobs.

• PERCS 2018.Ethical Hypothetical #18: Under-aged Drinking (embarrassing revelations).

• Wood, Elisabeth Jean. 2006. The Ethical Challenges of Field Research in Conflict Zones. Qualitative Sociology 29, 3: 373–386. [discusses challenges in getting informed consent and the procedures whereby the anonymity of those interviewed and the confidentiality of the data gathered were ensured during civil war constellations in El Salvador through a range of options]

Carte blanche when studying up?

Points to ponder / Buzzgroup

• Researchers in ‘underground’ settings, but also in investigative elite research have sometimes disguised their identities or purposes.

• Is it ethically justifiable not to disclose one’s research role when “studying-up” (elite) power or criminal structures?

• Discuss this quotation made by Gerald Berreman:

• “There is no scholarly activity any of us can do better in secret than in public. There is none we can pursue as well, in fact, because of the implicit but inevitable restraints secrecy places on scholarship. To do research in secret, or to report it in secret, is to invite suspicion, and legitimately so because secrecy is the hallmark of intrigue, not scholarship.” (Berreman1982:66; quot. in: Price 2015:103)

The American Anthropological Association in their 2012 Ethics Guidelines state:

[Researchers] “..should be clear and open regarding the purpose, methods, outcomes, and sponsors of their work.”

They must “..be prepared to acknowledge and disclose to participants and collaborators all tangibleand intangible interests that have, or may reasonably be perceived to have, an impact on their work.”

Researchers “… who otherwise engage in clandestine or secretive research that manipulates or deceives research participants about the sponsorship, purpose, goals or implications of the research, do not satisfy ethical requirements for openness, honesty, transparency and fully informed consent.” (AAA 2012)

Good reads:

• Nader, Laura. 1994. Up the Anthropologist—Perspectives Gained from Studying Up,” Reinventing Anthropology, Dell Hymes, ed., New York, NY: Vintage Books, 284-311.

• Gusterson, Hugh. 1997.Studying Up Revisited. Political and Legal Anthropology Review 20, 1 (May), 114-119.

• Wax, Murray, L. 1980. Paradoxes of ‘Consent’ to the Practice of Fieldwork. Social Problems, Feb. 27,3, 277f [for a vehement criticism to work with techniques of deception when “studying up”.]

• Price, David H.2015. Be Open and Honest Regarding Your Work. In: Plemmons, Dena/Alex W. Barker (eds.), 75-89.

“If your Research Design Includes Deception…”

Point to ponder:

• “Information for participants may be withheld from them only when the need to preserve the integrity of the research outweighs the participants’ interests, or if it is shown to be in the public interest.” (EC 2018a: 6)

• How does the anthropological position in the previous slide differ from the EC general recommendations for socials cientists(and why)?

The EC recommends:

“[…] provide strong justification for the choice of method by showing the importance of the research objective and demonstrating that your research cannot be conducted in any other way; describe how you will debrief your participants and retrospectively obtain their informed consent; show that the use of deception will not harm your participants socially, emotionally or psychologically and that revealing the real nature of the research will not lead to any discomfort, anger or objections on their part, and finally; obtain local ethics committee approval for your study before it gets under way.” (EC 2018a:Ethics in Social Science and Humanities, p.6)

Good reads:

• Calvey, David.2008. “The Art and Politics of Covert Research: Doing ‘Situated Ethics’ in the Field,” Sociology 42, no. 5, 905-918.

• Allen, Charlotte. 1997. Spies Like Us: When Sociologists Deceive Their Subjects. Lingua Franca 7, no. 9 (1997).

• Murphy, Elizabeth & Robert Dingwall. 2001. The Ethics of Ethnography, Ch. 23 in Atkinson, P, Coffey, A, Delamont, S, Lofland, J and Lofland, L (eds) Handbook of Ethnography, London: Sage [on the difficulty of always drawing a clear line between overt and covert ethnographic research]

Pitfalls in pseudonymization

Tips & Point to ponder

• the anonymity of critical questionnaires (this includes options for answers regarding the refusal of a measure requested by the government) is urgently required;

• if necessary, even the re-identification of interlocutors for subsequent interviews has to be eliminated.

• If repeated studies have been explicitly requested, the questionnaires have to be ‘depoliticized’ accordingly.‘(AGEE 2001)

Point to ponder:

is it ethically sound:

•…to conceal personal statements as “general scientific results”?

•…to depoliticize questionnaires?

In their Ethical Guidelines of 2001 the german Working Group on Development Anthropology (AGEE) points out:

“It is no problem to mention the name of a silversmith and his village in a research report about kinds of silver jewelry.

If one deals with the relationship between a community and a nation as a whole, it might be necessary to maintain anonymity of whole towns –if not to change the geographical locations (e.g. Syria, Morocco, Afghanistan, Sudan, Iran, etc).

A town of 2,350 inhabitants and 20% Christians as well as 10% Druses will be identified by the national secret intelligence agency within 10 minutes. If one adds a quotation by a sixty-year-old village sheikh who criticizes the government, the expert is likely to cause this person to be imprisoned very quickly.“

Possibly, one could conceal important, though compromising statements by representatives of target groups as general scientific results.” (AGEE 2001)

Anonymity of ethnographic data & law enforcement

On the power to compel testimony

Point to ponder

• The German Code of Civil Procedure (ZPO) regulates the right to refuse testimony based on office or profession.

• It applies in part to clergy, journalists, doctors, lawyers, notaries, tax consultants –but not to scientists.

• The case illustrates that researchers currently have no legal means of effectively protecting scientific data from access by the authorities.

• How do you estimate the danger to be called for testimony by authorities in your country (of research)?

• Do you have any idea how this could be bypassed in an ethically sound way?

Do we as social scientists have a legal right to refuse testimony?

- Legal psychologist Mark Stemmler and his team did research on Islamist radicalization in prisons in Germany in 2019. They interviewed prisoners and talked about their childhood, family, faith, the Koran, and politics -but not about crimes.

- For the recording of the conversations, the researchers assured the prisoners of confidentiality and secured the files in an encrypted and anonymized form. One of the suspects was believed by police investigators to be an alleged Islamist. Under threat of prosecution they confiscated a USB-stick recording of the interview with the scientists.

- In the meantime, the General Prosecutor’s Office has discontinued the investigations due to lack of proof. For Stemmler, however, the issue is not off the table. “I can only conduct the interviews if I assure the interviewees of discretion. One builds a trust. [..] If word of this gets out, I won’t have to go to prison anymore.” (DHV 2020)

- His lawyer filed a constitutional complaint in September 2020. [see: DHV.2020. Ermittler beschlagnahmen Forschungsdaten. Forschung& Lehre. cf.

Good reads:

• DBSH.2019. Right to refuse testimony -Brochure. [a petition for social pedagogy/social work].

• Scarce 1995. [for an earlier example of an American sociologist’s refusal to reveal the identity of his research participants which was then punished with 159 days in jail].

. Eppert, Kerstin et al. 2020. A Rugged Coastline. Ethics in Empirical (De-)Radicalization Research. Netzwerk für Extremismusforschung in Nordrhein-Westfalen. CORE NRW. Forschungspapier 1. https://www.bicc.de/fileadmin/Dateien/Publications/other_publications/Core-Forschungsbericht_1/CoRE_FP_1_2020.pdf. [encouraging (de-)radicalization researchers for open research practices in a way that the safety of research participants is guaranteed and the risk of reproducing and perpetuating radical/extremist narratives is minimized]

Anonymity of ethnographic ‘data’ and scientific evidence

Steven Lubet (Critic): “Why should we believe you?”

Alice Goffman (Author): “I was there!“

Goffman, Alice. 2014. University of Chicago Press. Cover (Photo: M. Schönhuth 2020)Goffman, Alice. 2014. University of Chicago Press. Cover (Photo: M. Schönhuth 2020)

Buzzgroup:

• Discuss the ethical dilemma between these two moral positions (Goffman/Lubet)

• Whose arguments are more convincing?

• How does this correspond with the ‘power to compel’ vs. the ‘right to refuse testimony’?

• “Goffman says she witnessed this interaction with her own eyes and was told in interviews with unnamed Philadelphia police officers that looking on hospital sign-in sheets for wanted criminals was a standard departmental procedure.

• Lubet doesn’t buy it, having spoken to a source in the Philadelphia Police Department who called Goffman’s account ‘outlandish’ and denied that any local hospital would have ever shared its sign-in sheet with the police.

• Goffman’s response is simple: I was there. Lubet’s is simpler still: Why should we believe you? [..]

• “As Lubet points out, she so disguised the people and locations that appear in ‘On the Run’ as to make her accounts effectively unverifiable. [..]

• What’s more, Goffman revealed in an interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer that she shredded all of her notebooks and disposed of the hard drive that contained all of her files out of fear that she could be subpoenaed and thereby forced to incriminate her subjects.”

(Neyfakh2015, in “The Ethics of Ethnography; Online Article)

Good reads:

• Neyfakh, Leon. 2015.The Ethics of Ethnography.

• TED Talks Alice Goffman

• Lubet, Steven. 2017. Interrogating Ethnography: Why Evidence Matters. Oxford University Press.

• Contexts. 2016. How to do ethnography right. Contexts 15, 2, 1-19. American Sociological Association. http://contexts.sagepub.com. DOI 10.1177/1536504216648145. [3 articles on the challenges of sociological ethnography today, one by Alexandra Murphy and Colin Jerolmackon “masking” in the era of data transparency].

Digital Ethnography

Is it ethnography at all?

Point to ponder:

• If we conceptualize ethnographic fieldwork as “[..]‘new’ sociocultural territory”, what if we…

• …study a place, filled with practices much like the one (we) come from –“…where technology is inextricably and unassumingly entangled in the everyday?” (Cupitt 2018)

• Can ‘digital ethnography’ be termed ‘ethnographic’ at all?

Tip:

BSA (British Sociological Association). 2016. Ethics Guidelines and Collated Resources for Digital Research. [with 6 intriguing case-studies and examples of ethics committee submissions from “Researching Online Forums”, to “ Using Twitter for Criminology Research’ to ‘Open Data and Democratic Governance’: https://www.britsoc.co.uk/ethics].

The self-deceiving digital ethnographer (according to de Seta 2018)

- The networked field-weaver: through everyday tracing of different actors, in various ‘media scapes’, the digital ethnographer weaves(or stitches) her ‘field’ together into a coherent networked (artificial) whole.

- The eager participant-lurker: “…a professionally naive explorer of local online contexts, master of all modes of participation, surveying digital media use from a vantage point of carefully crafted presence.”

- The expert fabricator: “…the accounts produced by digital ethnographers end up including an extremely narrow selection of inscriptions; […] the figure of the expert fabricator …easily overrides the messy, processual and thickly social construction of local expertise.” (de Seta 2018)

Good reads:

• Cupitt, Rebekah. 2018: We have never been digital anthropologists

• De Seta, Gabriele. 2018. Three Lies of Digital Ethnography

• Coleman, Gabriella, E..2010. Ethnographic approaches to digital media”. Annual Review of Anthropology. 39: 487–505. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.104945.

Ethical framework for ethnographic network research

Minimum requirements – maximum dilemmas

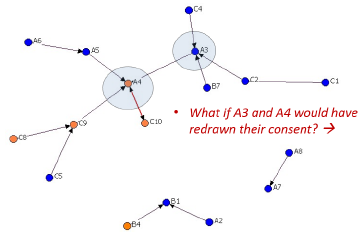

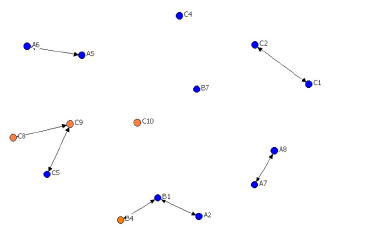

An informal whole network in a research cluster(question: „with whom do you regularly exchange thoughts beyond your own sub project?)“(©Schönhuth 2014)

…and how the network would look like, if A3 and A4 withdrew consent to be included (©Schönhuth 2014)

- Avoiding harm to innocents: only visualizing und publishing aggregated data, in a way that roles and positions can‘t be identified by insiders or clients, or participants

-> what if the network is too small to guarantee this? (see diagram on left) - Providing value to participants: feedback of own results as a minimal re-imbursement

-> but how to give back singular results without exposing other persons in the network? - Publishing network analysis results only, if people concerned are benefitting from it

-> what about ‘dark networks’ (terrorists, mafia, scientology..)? - In whole networks: leave it up to individuals whether or not they want to be included [„non-participation“]

-> but what if A4 and A3 in the graph on the upper left refuse to be included in your research (lower left)?

Good reads:

• Social Networks. 2005. Ethical Dilemmas in Social Network Research. [Whole issue]

• Kadushin, Charles. 2012. Understanding Social Networks. Theories, Concepts, and Findings. Oxford. Chap 12.

• Molina, José Luis & Steve Borgatti. 2019. Moral bureaucracies and social network research. Social Networks. [on the concern that with Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), social network researchers might limit their research decisions to only “safe” options].

Traceability in mediated settings

No choice whether to anonymize or not?

Point to ponder:

• Read the quote by Anne Beaulieu on the problems and dilemmas of anonymization she faced after her fieldwork in two laboratories on different stakeholder levels.

• What dilemmas arise?

• How would you cope with them?

Anne Beaulieu, in a note on her laboratory study, states that as a researcher in mediated /digital settings one may have no choice whether to anonymize or not:

• “Years after completing fieldwork at one of the labs that I had always been careful to anonymize in presentations and papers, Google would find traces of my presence as a user registered to the lab’s computer system.

• Furthermore, the ethnographer is not the only one who makes connections or cares about them: participants increasingly demand full citation or else make explicit the identity of the researcher in their own writing.

• A less positive side of establishing co-presence in this way is that it regularly creates friction with some editors and reviewers who feel that the moral valence of anonymizing is such that no circumstances warrant its suspension.”

(Beaulieu 2010: 465)

Good reads:

• Beaulieu, A. 2010. From co-location to co-presence: Shifts in the use of ethnography for the study of knowledge. Social Studies of Science, 40(3), 453–470.

• Stout, Noelle. 2014. Bootlegged: Unauthorized Circulation and the Dilemmas of Collaboration in the Digital Age. Visual Anthropology Reviews, 30,2, 177-187. https://as.nyu.edu/content/dam/nyu-as/faculty/documents/StoutVARBootlegged.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12047[on her failed efforts to control the unauthorized circulation of her documentary film on sex workers in Havanna].

Social Media Research and Ethics

Some Suggestions

Point to ponder:

Blurring boundaries between researcher and participant

• “Your own social media activity … may be part of the dataset you are researching…

• Also, the researchers themselves might become searchable by participants…” (Townsend/Wallace 2016: 11)

• Could you take precautions to adress these problems?

Blurred boundaries between public and private space and new modes of community and personal identity also pose new challenges in terms of consent, voluntary participation and vulnerability in mediated settings:

If you plan to use social media data in your research (European Commission.2018a)

• “Consult the relevant terms and conditions of the platforms you will be using to obtain your data.

• Appreciate that open source does not mean that it is open for use. Ascertain whether the data you intend to access is really public […]

• If the forum is closed, contact the site or group administrator.

• Seek permission from users […] and obtain their informed consent.

• Take […] precautions to avoid collecting data from children or vulnerable adults[…] without appropriate authorisations.

• Consider …whether users could be harmed if their data is exposed to new audiences […].

• Paraphrase all data that will be republished (to prevent others being led to the individual’s online profile).“(EC 2018a:9)

Good reads:

• Townsend, L/ C. Wallace. 2016. Social Media Research: A Guide to Ethics. The University of Aberdeen. [containing a framework for ethical research with social media data, and cases of ethic dilemmas, with possible ‘solutions’]

• Coleman, Gabriella.2014. Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous. London: Verso Books. [on her tricky inside–outside status of a ‘confidante, interpreter, and erstwhile mouthpiece’ of the Internet activist group anonymous].

• Samuel, Gabrielle and Elizabeth Buchanan. 2020. Ethical Issues in Social Media Research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics :1 –9.

• Hennell, Kath. 2019. et al. Ethical Dilemmas Using Social Media in Qualitative Social Research: A Case Study of Online Participant Observation. Sociological Research Online.

Fieldwork with all one’s senses

Making “being overwhelmed” functional

Buzz Group:

Overcoming sensory biases [Howes/Classen 1991]

The first and most crucial step: [..]”discover one’s personal sensory biases.” The second step: “training oneself to be sensitive to a multiplicity of sensory expressions.”[..] “The third step involves developing the capacity to be ‘of two sensoria’ about things, [..] which means being able to operate with complete awareness in two perceptual systems or sensory orders simultaneously.” [Howes/Classen1991:257ff]

• What have your sensory experiences been in ‘submitting your sentient body to the field of study’, so far? How did you cope with them?

• Are Howes/Classen’s tips helpful/realistic?

- On a field trip with our Trier students to South Indian cities, the hurdles in approaching the unfamiliar terrain, which some had to struggle with, consisted less in what they observed or heard, than…:

- …in the overwhelming (pleasant and unpleasant) smells ,the scorching heat, the deafening noise and the hectic pulse in the streets, the physical closeness and frequency of touching in public spaces, inescapable strong body odours, the (over)demanding and sometimes invasive conduct of street vendors or begging sadhus, as well as the tasteof spicy and hot meals, whereby the order: “only plain rice, please”, became a dictum.

—————————————————————————

- “[…]Wholly embracing sensory approaches to ethnography not only changes the nature of the study, it also changes the ethnographer.[..] [It] calls for ethnographers to submit their sentient bodies to the field of study.”(Stoller, 1989:39; cit. in Jackson 2018:9)

- Data which are central to research questions might be inaccessible to ethnographic observation (seeing) or interview (listening). How could we benefit ethnographically from our other senses?

Good reads:

• Pink, Sarah. 2010a. What is Sensory Ethnography? Lecture. Accessible on Youtube

• Pink, S. 2010b. Response to David Howes. Social Anthropology. 18,3,336–338.

• Howes, David and Constance Classen.1991. Doing Sensory Anthropology.

• Jackson, Thomas. 2018. Multisited ethnography. Sensory experience, the sentient body and cultural phenomena. The University of Leeds. [develops a fascinating new theoretical framework for sensory ethnography].

“Being parent in the field”: an intriguing anthology on how accompanied fieldwork effects on the immersion and one’s positionality in the field. This important topic would deserve its own “slide”. For the time being, the bibliographical reference must suffice:

Fabienne Braukmann, Michaela Haug, Katja Metzmacher, and Rosalie Stolz. 2020. eds. Being a parent in the field. Implications and Challenges of Accompanied Fieldwork. transcript publishing.

“Digital ethnography”: Based on a ten months research on digital rights activism in 2019/20 Benedict Mette-Starke in a 2-part blog post analyses Myanmar digital communication and discusses consequences for local scholars and others outside Myanmar. Cf.: Mette-Starke, Benedict. 2021. Avoiding Pitfalls in Engaging with Digital Myanmar: A Post-coup Analysis of Risk Mitigation. https://teacircleoxford.com/2021/03/15/avoiding-pitfalls-in-engaging-with-digital-myanmar-a-post-coup-analysis-of-risk-mitigation-part-1/.

Ethics in Forced Migration Studies: The International Association for the Study of Forced Migration (IASFM) in 2018 has launched a special “Code of ethics” with critical reflections on research ethics in situations of forced migration”: http://iasfm.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/IASFM-Ethics-EN-compressed.pdf

An update on these reflections can be found in a recent paper by Christina Clark-Kazak 2021.Ethics in Forced Migration Research:

Taking Stock and Potential Ways Forward” Journal on Migration and Human Security 2021, Vol. 9(3) 125-138. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/23315024211034401