IV. Negotiation

The Ethics of Reciprocity

How much ‘bonding’ goes with ‘connecting’?

© “The bill please!” Schönhuth 2020

“When doing fieldwork, we are not only asking people to take time to work with us, we are also asking them to trust us. Each relationship we build with an informant is different, but all are implicitly reciprocal. Identifying exactly what our obligations are to our informants is perhaps the most crucial step we take in ensuring we act ethically.” (PERCS 2018)

Point to ponder: What kinds of reciprocity do you know?

Buzz Group:

After a joint visit to the restaurant: Are you paying jointly (one bill for all) or separately? What rules apply, where & when? In Germany? In your country/ other countries?

Good reads:

• Hann, Chris. 2006. The Gift and Reciprocity: Perspectives from Economic Anthropology. Handbook on the Economics of Giving, Reciprocity and Altruism.

• Mauss, Marcel 1925 (1970). The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. London: Cohen & West. [The classic]

• Rus, Andrej (2008).”‘Gift vs. commodity’ debate revisited”. Anthropological Notebooks 14 (1): 81-102. [A revision of the classic].

• Claridge, Trsitan.2018. Functions of social capital –bonding, bridging, linking. Social Capital Research.

Obligations to interlocutors/research particpants

Compound discussions with the village healer on local health issues © Schönhuth 1997 (East-Tanzania)

Buzz Group:

• The Golden Rule principle of treating others as you want to be treated applies to most ethical issues, but here it is particularly useful as a starting point:

• If you were the research participant, what would you expect from the researcher you were working with? What would be a fair return for assistance? …:

• Direct Compensation?

• Maintenance of contact after project ends?

• Sharing of all data with you?

• Other returns you know or?

• Did they work?

Good reads:

• On ethical implications of being offered a stolen gift. Stone, Rose: „Hot Gifts.” Ethical Dilemma. Stones’ Response and readers# discussion

• On ethical implications of a “Shared Cultural Ownership” see. La Folette, Laetitia (ed.) 2014: Negotiating Culture. Heritage, Ownership, and Intellectual Property. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press.

• On financial compensation: Arunkumar A.S., Deverapalli J. 2014. Paying informants in Ethnographic Research. In: Biswas Subir(ed.) Ethical Issues in Anthropological Research. Concept Publishing Co, Delhi, 45-55.

Complicity in ethnography as default setting?

Neo-Nazi rally in Munich on April 2, 2005. Rufus46 -CC BY-SA 3.0. Wikimedia Commons

- As long as one researches “down”the power structures, with disadvantaged, marginalized people, showing sympathy or even solidarity with them and advocating for them seems ethically sound.

- But what, if we study up, towards powerful, radical or even unlawful/criminal structures?

- Benjamin Teitelbaum, who spent 10 years researching on right wing groups in the Nordic countries, defends scholar-informant solidarity in ethnography as “…morally volatile and epistemologically indispensable. Seldom can we campaign against the people we study while collaborating and engaging with them personally, yet it is through exchange and partnership that we gain our signature claims to knowledge.” (Teitelbaum2019)

Point to ponder: Can we “dance with the wolves” (Hübinette 2019), without howling with them; or do we always need a ‘detached’ form of observation in “studying up”, as Laura Nader (1974) put it, to stay ethically unblemished? What does Teitelbaum mean with “our signature claims to knowledge”?

AAA Code of ethics on researchers obligations over the years:

- “In research, anthropologists paramount (1970) / first (1990)/ primary (1998) responsibility is to those they study.”

- (2012):”Anthropologists must weigh competing ethical obligations to research participants, students, professional colleagues, employers and funders, among others, while recognizing that obligations to research participants are usually primary.”

- Point to ponder: Discuss the semantic shifts in the different versions. What is the fundamental change in the 2012 version?

Good reads:

• Teitelbaum, Benjamin R. 2019. Collaborating with the Radical Right. Scholar-Informant Solidarity and the Case for an Immoral Anthropology. Current Anthropology 60,3. Forum on Public Anthropology (with discussants): https://www.benjaminteitelbaum.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CA-article.pdf.

• Nader, Laura. 1974 (1969). Up the Anthropologist —Perspectives Gained From Studying Up. In Dell Hymes(ed.) Reinventing Anthropology, New York, pp.284-311.

• Dauphinée, Elizabeth. 2007. The Ethics of Researching War: Looking for Bosnia. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [discusses the possible responsibility not just to victims of war, but also to the perpetrators of violence in Bosnia.]

Expectations of reciprocity beyond the end of research

Point to ponder:

• “In 2009, when I returned to Rwanda to begin interviews for a new project, many of the prisoners I had interviewed in 2004 had been released. I went to talk to several of them at their homes.

• [..] Despite a lengthy, verbal consent protocol that included all the usual caveats about there being no payment for their participation, many continued to ask for various forms of assistance.

• One asked for help finding a job, another for help paying restitution to genocide survivors whose property had been stolen during the genocide. Another told me bluntly that he expected quid pro quo”assistance” because I had published a book from the information he and his fellow prisoners had provided and was surely making money from that book.” [Fujii2012:719]

The system of owed gratitude -utang na loob in the Philippines:

• hierarchical system of mutual, often lifelong, but informal relationships of favor and obligation between a patron and his clients

• translated by locals to development experts and institutions as reciprocity offer: ‘participation’ of the clients in project activities for ‘lifelong’social caretaking and favors by the project

• consider the consequences for clients when the project ends and researchers / experts leave the country… (Source: Teves, Lurli. 2000).

Buzz Group:

How would you cope with expectations of reciprocity after the end of fieldwork?

What and how much can we promise? (PERCS 2018)

Tips:

• “One way to avoid one-time guarantees is to ensure that you don’t engage in one-time fieldwork.In other words, your work with participants should generally extend beyond a single interview, even if it simply means a thank you note or a follow up phone call.

• Maintaining some degree of contact makes it much easier to alert participants to any important changes in the project.

• There will also be times when the research focus changes but you feel it does not affect the initial consent that participants gave. Before assuming too much, you may want to check with one or two of your closest participants.” (PERCS 2018)

- “In our informed consent statements, we often outline what participants will be asked to do, what they will receive in exchange, and how we will protect their confidentiality.

- But as the conditions around us change, we may discover that we cannot adhere to all of the things we promised.

- Further, it may become evident that we have discovered new questions that are more central to our understanding.

- How can we keep our participants abreast of our current thinking and the shifts in our research questions or practices? How can we think of informed consent as being an ongoing process of negotiation rather than a one-time guarantee?” (PERCS 2018);

Good reads:

• du Toit, Brian M. 1980. Ethics, Informed Consent, and Fieldwork. Journal of Anthropological Research36, 3, 274–86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3629524. [The classic on informed consent and fieldwork).

• Annechino, Rachelle. 2013. The ethics of openness: How informed is “informed consent”? Ethnography matters (Online Journal): https://ethnographymatters.wordpress.com/2013/03/01/the-ethics-of-openness/. [On how such Informed consent is less about forms, than about relationships between people and trust.]

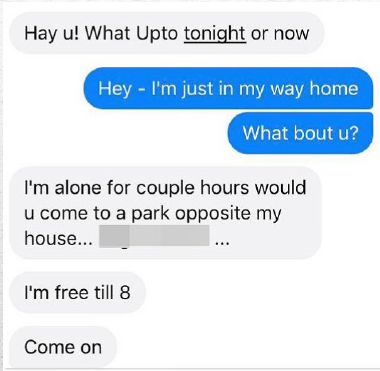

Indecent reciprocity offers

Trying to do fieldwork in an androcentric-dominated environment

(Johnson, Lisa. 2020. Moves, Spaces and Places: Roots, Pathways and Trajectories of Jamaican Women in Montreal. Dissertation. University of Trier)

extract from a messenger chat(field researcher’s part: blue; © Lisa Johnson 2020);

reprint with kind permission of the author.

- “However, from the beginning of my research phase I faced major difficulties in approaching men as a female researcher.

- It was complicated to… talk to men –aside from discussions surrounding their careers –or to build up trustworthy professional relationships in general. Men will small talk about work or hobby-related topics, but it was impossible to discuss private aspects of their lives openly.

- It was extremely hard to get into contact with men in semi-public social spaces without being flirted with or ensnared in the androcentric-dominated [world].” [Johnson 2020]

• Point to ponder: How would you have (re)acted in her place as a female researcher in the field?

• Buzz Group: If you are a gender mixed group, divide yourself into gender-homogeneous subgroups and compare your discussion results afterwards.

Dangerous liaisons – risk, positionality and power in women’s anthropological fieldwork

Tips:

promoting gender-based safety in fieldwork

-> Listen to the voices of those community members with whom you have developed the most rapport.

-> Find your ‘mother’ (or whomever might fall into this category) whom you can ask for advice and assistance when needed.

-> Recognize own multiple and shifting roles (relatively powerful western anthropologist, vs. vulnerable to sexual harassment and assault), and how they articulate with overlapping layers of power and inequality in the fieldwork context within and between local communities and the outside world) (cf. Miller 2015: 85-86)

- “Schooled in post-1980s reflexive anthropology, I was acutely sensitive to the exploitative potential of the situation. I often felt like a vampire, sucking stories out of my informants, living and feeding off the blood of their lives.

- Thus, when informants demanded something of me in return for their participation –money, a small gift, help with finding a job, assistance with their child’s education, etc. –I was often relieved[…]

- With male informants, however, my desire to fulfil reciprocity expectationsplaced me in a position of vulnerability. Many men made it quite clear what they wanted in return for their participation… I felt paralysedby my desire to be a ‘good anthropologist’.”(Johansson 2015:58)

Good reads:

• Metooanthro.n.d.[2020] A collection of resources about the issue of sexual assault and harassment in anthropology. [a site with an abundant up-to-date collection of resources about the issue of sexual assault and harassment in anthropology]

• Quinn, Naomi. n.d.What to Do About Sexual Harassment: A Short Course for Chairs.

• Johansson, Leanne. 2015. ‘Dangerous liaisons: risk, positionality and power in women’s anthropological fieldwork’, Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford7,1, 55-63.

• Hanson, Rebecca and PatriziaRichards. 2019. Harassed:Gender, Bodies, and Ethnographic Research. Oakland: Univ. of Calif. Press[argues against publically held ‘ethnographic fixations of ‘good’ ethnographic research, which should be solitary, dangerous and characterized by intimacy with the participants].

Friendship and Fieldwork

Romancing Rapport?

Buzz Group:

How would you like to shape personal relationships with interlocutors / key informants in the field: in terms of a…

• …methodological, ’empathic’ tool?

• …temporary friendship, with benefits for both sides?

• …an ongoing relationship with obligations long after the end of the fieldwork?

• Weigh for and against for each of these options.

• Do you see options to escape from Hatfield’s triple roles, being trapped as ‘fool’, ‘Fort Knox’ and ‘Sahib’?

• Can friendship be ‘negotiated’ at all?

- Driessen(1998) states that “the rhetoric of friendship often [..] operates to conceal the strains involved in the unequal power balance between fieldworkers and informants” [:132]

- Hatfield (1973) speaks of asymmetrical mutual exploitative constellations with the researcher in the triple role as: incompetent fool (stranger, child, or pawn), ‘Fort Knox‘ (reflecting her/his perceived wealth), and ‘Sahib‘ (apparent class-hopping skills between state/academic circles and local community, world traveler and cultural transvestite).

- Tillmann-Healy (2003) wrote in defense of friendship as a methodological tool, as a firm base for empathic understanding.

- For van der Geest”friendship developed in the course of research, ‘because of the research’. [..]It was through my persistent questions, they said, that they had seen new things in their taken for granted day-to-day lives.” (van der Geest2015: 7)

Good reads:

• Hendry, J. 1992. The paradox of friendship in the field. Analysis of a long-term Anglo-Japanese relationship. In: Judith Okely& Helen Callaway eds. Anthropology and Autobiography, 163-174 .

• Hatfield, Colby R. Jr. 1973. Fieldwork: Toward a Model of Mutual Exploitation. Anthropological Quarterly, 46:15-29.

• Driessen, Henk. 1998. Romancing rapport: The ideology of ‘friendship’ in the field. Folk,40, 123-136.

• Taylor, Jodie.2011. The Intimate Insider: Negotiating the Ethics of Friendship When Doing Insider Research. Qualitative Research, 11,1, 3–22.

• Van der Geest, Sjaak. 2015. Friendship and Fieldwork: A Retrospective as ‘Foreword’. Curare 38, 1+2, 3-8.

• Tillmann-Healy, Lisa M. 2003. Friendship as a method. Qualitative Inquiry, 9,5, 729-949.